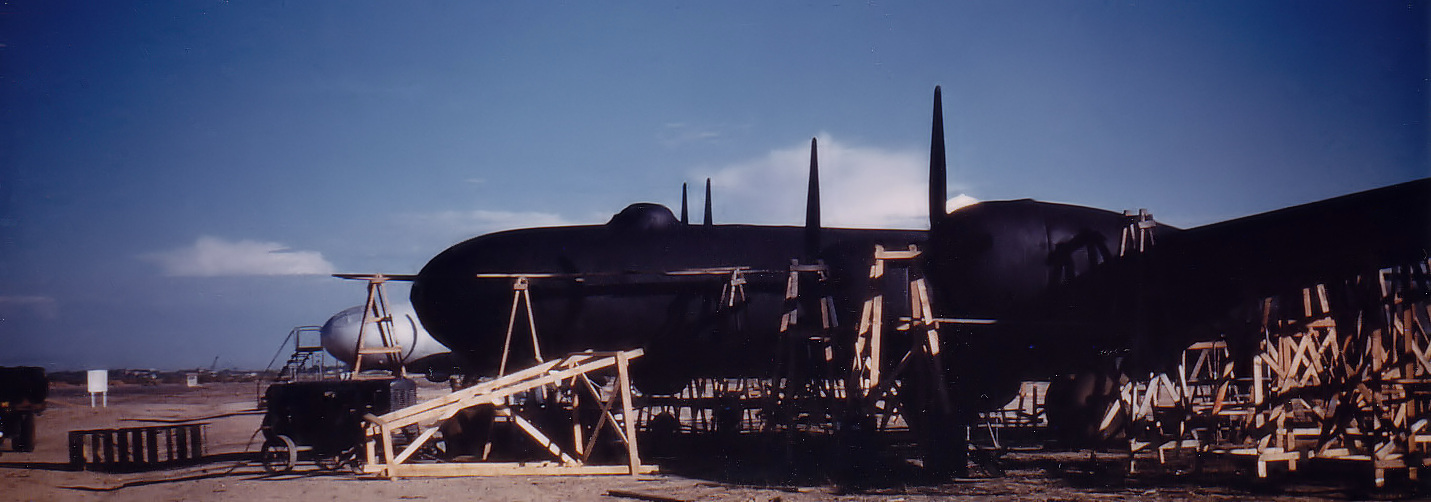

Title Picture: Rows of B-29 Superfortresses in storage at Davis-Monthan AFB.

Photo from the Colonel Schrimer Collection.

The End of World War II

On May 7th 1945 the German Armed Forces High Command formally signed a document which agreed to the unconditional surrender of the German forces in Europe and North Africa to the Allies. This was followed a few months later by the formal surrender of Japanese forces in the Pacific on September 2nd 1945. These events brought World War II to a close after 6 long years of conflict.

Immediately following the cessation of hostilities tens of thousands of US military aircraft, which had been essential to the allied victories, suddenly became a substantial problem. Out of the vast numbers of aircraft that had been built for the war effort, estimated at being around 295,000, some 150,000 were still in service. This was far more than required and could be financially sustained during peacetime, the question was what was to be done with them. Starting earlier in 1944, the U.S. Foreign Economic Administration had begun disposing of damaged and obsolete aircraft located overseas, but, a solution for the remaining numbers was urgently investigated.

An initial decision was to collect the surplus aircraft at 30 depots which were established around the USA by the Government's Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). These depots were split between those that would act as longer term storage sites and those depots that would store aircraft for the short term. These depots would also dispose of all the surplus and obsolete aircraft by sale or scrapping.

| Short Term Storage & Disposal | Long Term Storage Depots | |

|

|

Dealing with the problem

The advancement of aircraft designs which had been accelerating during the final years of the war and into the second half of the 1940s had meant that the aircraft types in service were becoming obsolete at an increasingly frequent rate. Even many of the most advanced piston powered fighter aircraft had become obsolete due to the introduction of types that were powered by jet engines. The heavy bombers that were so effective during the war, including the B-17 and B-24, had been replaced by the much larger and more capable B-29. The long term storage of many of these types for future by the United States military was not an option, the answer was to sell off what could be sold and to scrap the rest. The War Assets Administration (WAA) was established in 1946 to dispose of much of the now surplus war equipment and supplies, including the unwanted stock of aircraft. The United States had learnt, following the end of World War 1, that if this enormous quantity of resources was released in an uncontrolled manner it would severly impact the recovery of peacetime commercial activities, especially the important aviation industry.

It was important that the stock of surplus aircraft should be disposed of quickly in a method that not only returned a realistic proportion of the original cost back to the Government but also stimulated new markets and businesses. Once this rapid disposal had completed it was hoped that new aircraft designs would once again start to roll off of the aviation industry's production lines.

Disposal

In 1944 a sale of over 5,000 Government owned training aircraft, used by contract companies to train civil pilots, proved that there was a strong demand for surplus aircraft by the general public if the price was right. This sale had been a huge success, with over 40,000 bids entered into the sealed bid system even though there was not a publicity campaign run to advertise it. There was however, a big difference between the types of aircraft involved in this sale and the military aircraft types available after the war. This time purchasers would be confronted with work and additional costs to bring them up to a standard suitable for operation by civilian operators. To prevent a potential flood of dangerous aircraft types entering into public ownership the Civil Aeronautics Administration, in co-operation with the WAA, carried out testing on the types included in the surplus stock to establish those eligible for civil certification. Some types which did not reach the required standard would be sold, but, with a condition that certain modifications be made before certifcation was issued for them.

Much of the wartime restriction of flight within the US had been lifted and the appetite for aviation was as strong as ever. By September 1946, the WAA had sold off close to 64,000 aircraft to new civilian owners. The quantity of aircraft being disposed of was so large, that the sale price achieved for some of the smaller types was less than the cost of an average family car. An example of sales prices achieved include...

- Beech AT-11 - Between $7,500 and $15,000

- Boeing PT-17 - Between $250 and $1,830

- Fairchild PT-26 - Between $750 and $2,150

- North American T-6 Texan - $850

- Vultee BT-13 - $200

- Vultee BT-15 - $450

New and emerging flying schools, which had spawned from the educational provisions in the G.I. Bill of Rights, purchased in total 17,000 primary and advanced training aircraft. On January 1st 1946 a total of 405 flying schools were in existence. In September of the same year that number had leaped to 1,281. Light Liaison aircraft, like Grasshoppers, Cubs and Flying Jeeps, accounted for one seventh of all sales. Many went to flying school and into private ownership. 3,000 large and medium transport aircraft, including 550 C-47 Skytrains, 20 C-54 Skymasters and 12 twin engined Lockheed freighters were sold to companies in a developing air cargo transportation industry. More than 100 transport aircraft were also purchased by existing airlines, boosting their fleets to cope with the increasing quantity of air travel now being undertaken.

In addition to over 4,600 commercial flying businesses, many supporting enterprises including parts supply companies, repair shops and handling agents were also being formed at an impressive rate. In time some of the thriving commercial flying companies would place orders for new replacement aircraft and this would spread the growth into America's aircraft manufacturing companies.

Most of the aircraft which were not suitable for civilian use, including tactical fighters, bombers, and the special use types, were sold for scrapping, salvage or non-flight use. 21,000 tactical aircraft were offered for sale by sealed bid at five major storage deports. To ensure that the resulting nationally required metal would reach the markets without delay, there was a stipulation that the aircraft had to be processed within 18 months of successful purchase. In total 104 sealed bids were received and the aircraft awarded to the 5 with the highest offers. The sale resulted in over 200 million pounds of aluminum alloy and other metals, which were sorely needed in the flourishing housing and consumer industries.

While most value from the tactical aircraft types came from their metal content, a large number were also supplied to some 2,800 technical schools that purchased over 1,000 tactical aircraft, 3,000 aircraft engines and 300 navigation and instrument trainers. The revenue recovered by the sale of such a small percentage of the surplus stock was small, the value to the country in terms of re-training capability was immeasurable.

A smaller number of tactical aircraft were supplied to local governments for use as war memorials. Included in these sales was Seattle, WA. that purchased a B-17 Flying Fortress called 'Five Grand', the 5,000th B-17 off of Boeing's production line in the city. The famous B-17 'Memphis Bell' was purchased by the City of Memphis, TN. and Athens, GA. purchased a total of eleven aircraft to form their own museum.

The disposal of surplus aircraft was nearly complete by the end of 1947. It had been managed in a way that had injected a massive boost to the US economy and stimulated a large growth in commerce. This was urgently needed to recover the country after the expensive and economically damaging years of war.

Summary of Post War Dispositions

The table below shows the total number of excess Air Force aircraft disposed of for the years immediatly following WWII. The 'Transfers' were the aircraft transferred to the WAA and other Government agencies for disposal by commercial means, the 'Scrap and Other' figures are for the aircraft which were scrapped or turned over to instructional use by the Air Force themselves.

| Type of Disposition | Total | Prior to 1945 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | |||||

| 1st Qtr | 2nd Qtr | 3rd Qtr | 4th Qtr | Total | Jan - Aug | Sep - Dec | ||||

| Transfers | 51,027 | 14,667 | 5,919 | 4,068 | 8,845 | 11,257 | 29,789 | 5,308 | 934 | 329 |

| Scrap and Other | 8,504 | 326 | 282 | 1,010 | 298 | 2,739 | 4,329 | 3,545 | 287 | 17 |

| Air Force - Total | 59,531 | 14,993 | 6,201 | 5,078 | 8,843 | 13,996 | 34,118 | 8,853 | 1,221 | 346 |

For a more detailed look at which aircraft categories were stored and disposed of between 1945 and 1947 please use the links on the right of this page under the heading 'Surplus U.S. Air Force Aircraft By Aircraft Type'.

Following the Mass Dispositions

During the following decade, the quantity of aircraft being stored at the other major facilities would see a major reduction. The disposal of obsolete aircraft types had mainly been completed. The work carried out at the longer-term storage bases concentrated on the storage of viable types and reclamation of parts, to keep the active fleet airworthy.

Initially, Davis-Monthan AFB was one of the smaller storage bases, mainly used for Boeing B-29 Superfortresses and C-47 Skytrains. However, during the mid 1950s the larger bases, including Kelly AAF, TX., Pyote AAF, TX. and Tinker AAF, OK. closed or relinquished their major storage mission and the primary responsibility was handed over to Davis-Monthan AFB.